Where the Floor is Really Lava

This was originally written for The Cut, as part of a series on raising boys. This version is longer, containing more details about my son’s worlds. You can read the original, shorter version here.

My dad left us when I was 2, owing to a drug habit he wouldn’t or couldn’t break. I was young enough that I have only a handful of memories of him, and I hardly ever felt conscious of his absence during my childhood. My mom spoke of him rarely, but there was one topic likely to trigger his mention: video games.

Her own positions on the subject seemed to be in conflict. In line with the dominant view of the ’80s and ’90s, she saw video games as time wasters that produce horrible bleeps and bloops and turn your brain and body to mush, a feeling borne out by her own experiences of trying to play games with me. But video games were also a deep interest of mine that she was sure my father — an engineer and tech buff — would have shared, a fact she would note in an apologetic tone.

Most of my childhood friends were also boys with single mothers, and video games played a similarly contradictory role in their lives. Yes, they were indulgences. But they were also babysitters, being one of the more reliable methods for a group of young boys to be left unattended for hours with little risk of injury or property damage. As a parental substitute, video games from that era taught a kind of mental athleticism: reflexes and coordination, practice and perseverance, self-improvement and competition. But in the absence of a coach, this kind of athletic stress didn’t produce the camaraderie one might see in physical sports. My friends and I would fight over turns, throw controllers, make hostile accusations of “being cheap,” and so on. Once, a friend yelled at me for having breathed too audibly while he played a hard level of Batman. Since it was his Nintendo, he decided I would from then on hold my breath during his turns, lest I corrupt his delicate focus. Not exactly a model of grit.

So when I imagined playing video games with my son — now 6 — I pictured myself as being the Player 2 that I’d never had in my own childhood. I wouldn’t mind which games he wanted to play, or how many turns he’d take. I would comfort him through frustrating losses and be a good sport when we competed head-to-head. What I hadn’t anticipated in these fantasies was how much a new breed of video game would end up deeply altering the way we relate. Games of challenge and reflex are still popular of course, but among children my son’s age they’ve been drastically overtaken by a class of games defined by open-ended, expressive play. The hallmark title of this sort is, undeniably, Minecraft.

Minecraft presents the player with a rich, interactive world composed entirely out of simple LEGO-like blocks. You can explore and discover new lands, or settle in an area to build tools and structures for yourself. But playing Minecraft doesn’t actually feel much like playing LEGO, nor does it feel much like playing the video games of my childhood. Instead, a better point of comparison is the sort of make-believe roleplaying kids do with each other, like playing house. In Minecraft, the imaginary worlds my son dreams up are expressed and realized in a virtual environment multiple people can occupy and affect together. When he tells me the floor is lava, I look down and notice that the floor is indeed made of burning lava, fatal on contact. In response, I construct a bridge.

My son and I do still play those competitive games, and I hope that he’s learning about practice and perseverance when we do. But those games are about stretching and challenging him to fit the mold of the game’s demands. When we play Minecraft together, the direction of his development, and thus our relationship, is reversed: He converts the world into expressions of his own fantasies and dreams. And by letting me enter and explore those dream worlds with him, I come to understand him in a way that the games from my childhood could never offer.

Touring the worlds that my son has settled over the last couple of years, I find a lot of the imagery one might expect from a kid his age. Throughout are standard fantasies like living in a treehouse or on a boat. The dominant themes vary as I pass through time: trains in his earliest worlds, then robots, a long streak of pyramids. Pirate ships, particularly half-sunken ones with treasure chests, remain a constant.

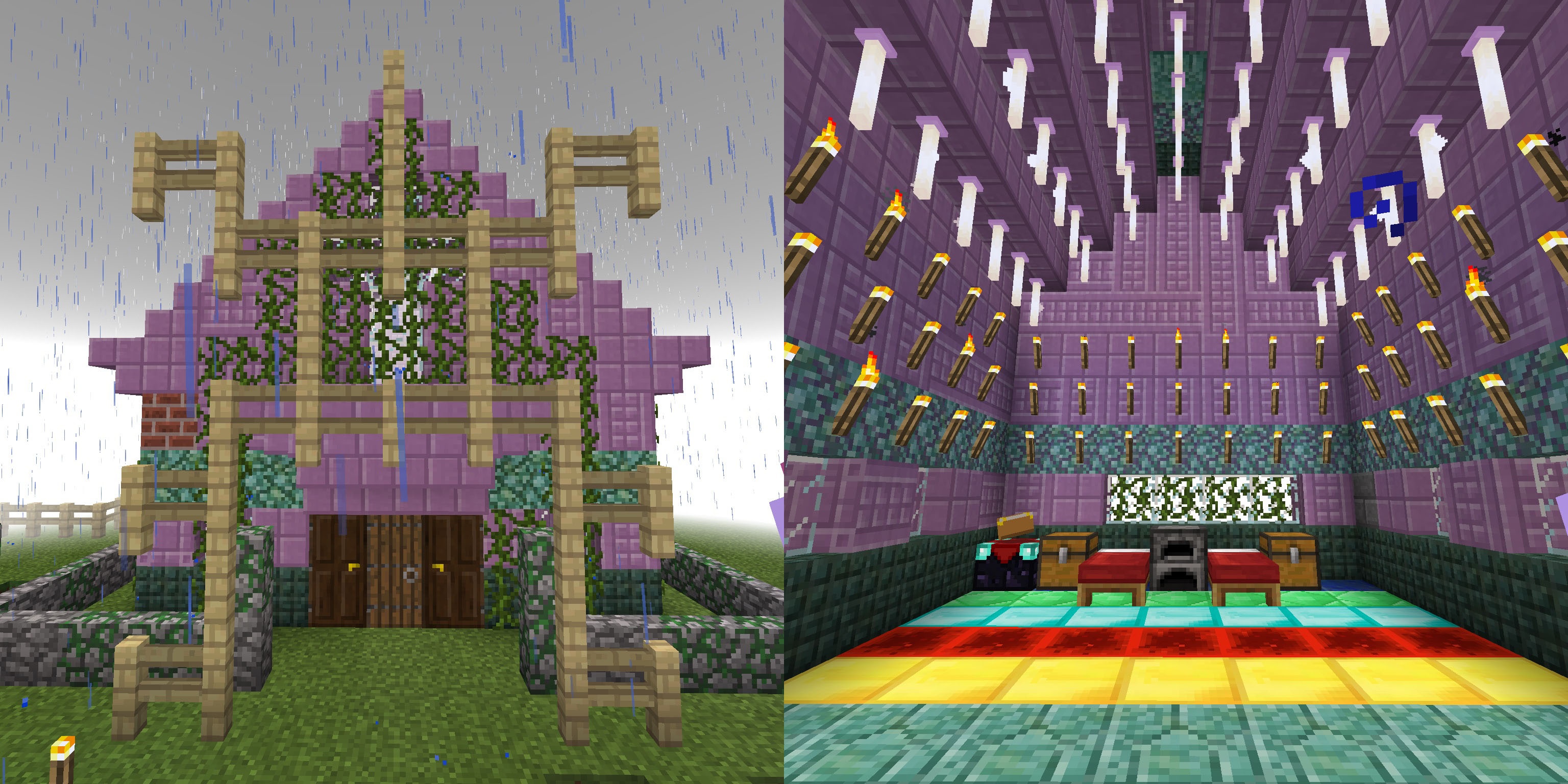

As his choice of imagery evolves, so too does his technical prowess. Records of his old worlds are saved forever, so I can walk among his trials, errors, and eventual fits of progress. Crude box houses on flat terrain later become winding complexes with staircases and secret tunnels, increasingly incorporating and responding to the natural environment. He learns to control water, masters 45° angles, discovers the concept of scaffolding — the archaeological history of a civilization of one.

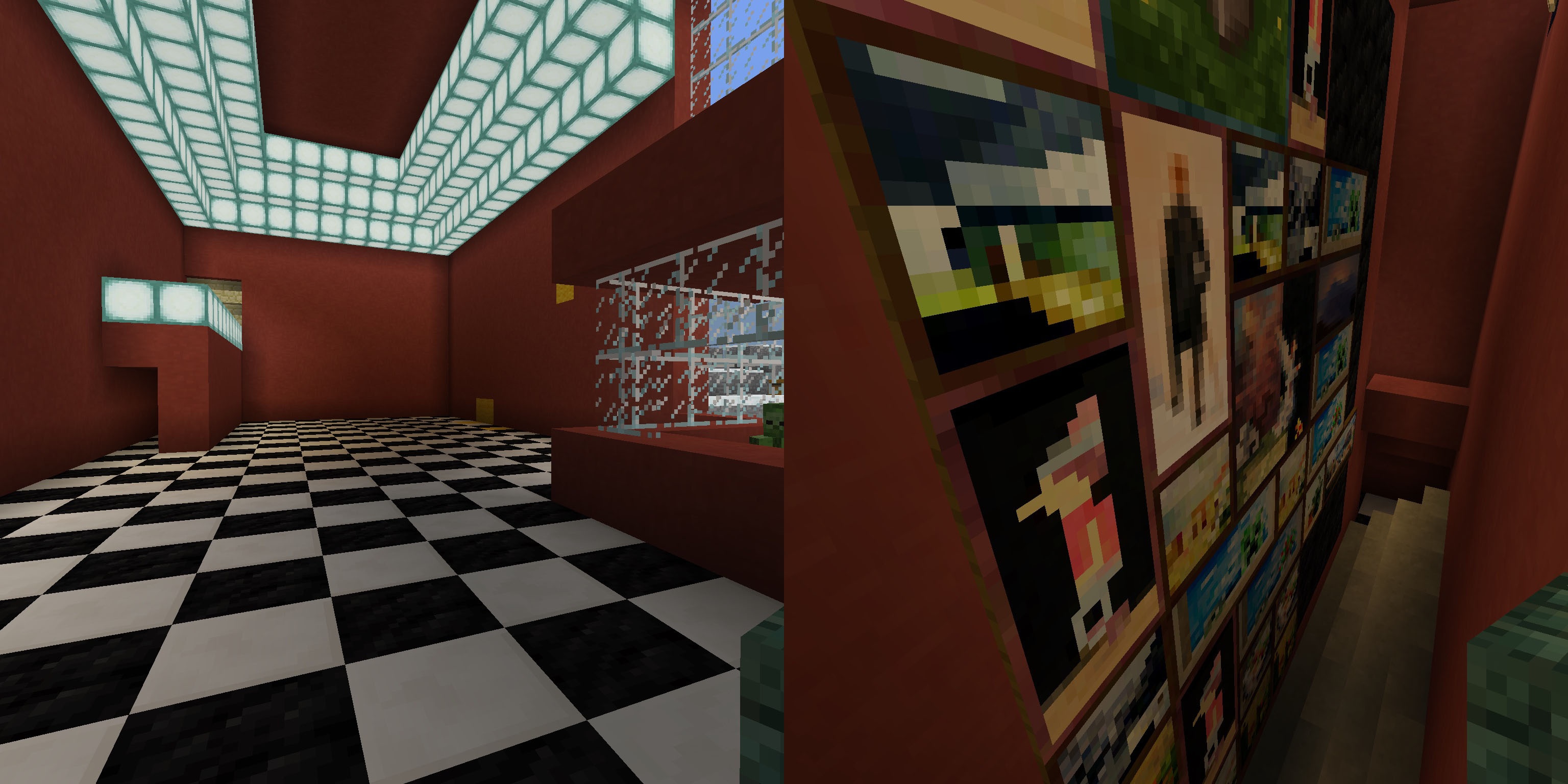

In the days following a trip or event, he might build a re-creation of wherever we went. I recently visited his interpretation of a movie theater, complete with popcorn machines, a box office, patterned floors, and cavernous ceilings. Many details are incorrect or arbitrary and yet the impressionistic “theater-ness” comes across anyway. The auditorium itself is a huge screen flush against a single row of seats — impossibly narrow yet consistent with the only details retained in a young memory.

Often his worlds are littered with failed experiments, unfinished projects, or ideas that almost certainly emerged from the pure subconscious. The best of these can be visually arresting, not too many steps away from high-concept installation art. A pyramid of TNT draped in regal banners, a beachside human form comprised of candles, a statue's legs with a dozen potted cactus in place of a torso. He seems to understand that these constitute little moments for his visitors, as many will have signs declaring the “title” of the “work” as in a piece called train crash, which features dozens of minecarts carefully composed around a track, some floating impossibly in the air. If I ask about his intentions, he often can't explain himself or has already forgotten by the time he's finished. The work must speak for itself.

In Minecraft, you often need to build a semi-functioning house with working features like a bed and storage, which means I get to see my son’s personal ideas about what “home” should feel like. Going through these houses, a number of motifs come up again and again: He loves extreme symmetry, varying bands of bright colors, and elaborate lighting comprised of dozens of fixtures. His precise and idiosyncratic tastes are balanced by his fondness for family; he typically incorporates multiple beds and bedrooms, reserved for different family members that he pretends might visit one day.

And I do visit periodically, to take the guided tour through his work or to play alongside him. In the beginning I mostly built structures on his request, like a submarine we could pretend to operate. These days we prefer to homestead, splitting up responsibilities between harvesting wheat, collecting cattle, making improvements on our house.

The working rhythms of our shared play allow for stretches of silent collaboration. It’s in these contemplative moments that I notice how distinct this feeling is from my own childhood, as well as the childhood I had predicted for my son. I thought I would be his Player 2, an ideal peer that would make his childhood awesome in ways that mine was not. In retrospect, that was always just a picture of me, not of him and not of us.

My daughter just turned 2, too young for video games. When she’s ready, will she be an explorer or an architect or a storyteller? Will she prefer simple homes or will her tastes be more fantastic? What shared dreams will she author with her brother, or with me? And when they’re both much older, how will it feel to load up their worlds again and walk around inside of their own childhood fantasies? When I look forward to playing games with her in the future, the picture in my head doesn’t look like my childhood anymore. In fact, the picture can’t be filled in at all — she still has to build it.